Reclaiming Compassion in Society is the Path to Healing a Divided World” By Dr Umar Al-Qadri

As a person of faith, I believe faith to be something liberating, something that gives joy in our times of happiness and solace in our times of sorrow. A lack of empathy in religious people – worse, visibly religious people, and worse still, religious leaders or the clergy – has throughout the world turned people away not only from the formal structures and hierarchies of faith (perhaps not a bad thing) but from faith itself.

Because when we think of religious people, empathy definitely isn’t the first thing that comes to mind. There’s a concept of religious people as harsh, conservative or judgemental. Whether it be in the history of my country, Ireland, and the generations of priests and nuns who limited life opportunities for single mothers, or whether it be in the contemporary troubles of Afghanistan, with the Taliban limiting women’s rights in pursuit of supposed religious purity, empathy is definitely not high enough on our collective religious agendas. As a person of faith, a faith leader, indeed, this makes me sad.

All religions in their truest form have empathy at their core. Indeed, so central is empathy to true faith and religion that it has been called “the golden rule” – be it the “Love for your brother what you love for yourself” of my faith, Islam, the “Do unto your neighbour as you would have done unto you” of Christianity or the near identical commandment found in all nearly all major and minor religions in the history of the world, there is no faith without empathy.

Gifts and gestures do not always cross linguistic, cultural and theological boundaries and borders well. A simple thumbs up, a seal of approval throughout most of the world, is an offensive gesture in parts of Afghanistan. Candles are a semi-passive form of remembrance and hope in Catholicism, an active form of ‘fire-worship’ in Hinduism, and yet considered a superfluous extravagance in strands of Protestantism and Islam. Throughout the Western world, the bride wears white on her wedding day – in the Indian subcontinent, the Hindu widow wears white to symbolise her grief. You are beginning to understand how difficult it is to find a single, universal gesture of solidarity and compassion, of our siblinghood in the human family, that translates well to all times and places.

It is this universality of empathy that makes it so essential as we navigate our way through this complicated world. Everyone, regardless of their language, background, creed or absence of, or economic status can understand empathy. It is a gift we can confidently give and receive wherever we find ourselves in the world, even when separated by issues of communication and language.

Empathy is universal in other ways too: it need not be an in-person experience – we can feel empathies for individuals whether they are known to us or strangers, friends or enemies. A well-known example from the life of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) comes to my mind, when he told his companions, “Assist your brother, the oppressor and the oppressed.” Confused, his companions asked him, “How do we assist the oppressor?”, to which he replied, “By stopping him.” We can widen this analogy out to our approach to crime and social exclusion in our societies.

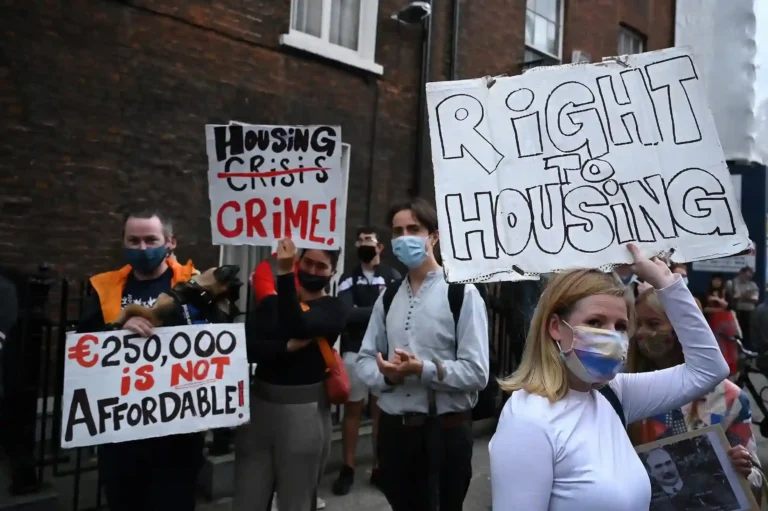

There is no doubt that crime and anti-social behaviour causes great harm in our societies. But rather than merely seek to condemn, we can take an empathetic approach, seeking rehabilitative and restorative approaches to justice that make us all safer by preventing crime at its roots, rather than the reactionary calls for ever punishments that cloud our conversations at every level of society, from social media to our political establishments.

We can feel empathy for groups, societies and entire nations too. This is even more important in an age of twenty-four hour news coverage, digital and social media, when constant exposure to tragedy and trauma threatens to desensitise us. At the time of writing, wars have raged in Syria for over ten years, whilst children starve to death in Yemen on a daily basis. The people of Palestine continue to suffer whilst no solution appears obvious. The pandemic appears to be entering its end game in Europe and the developed world, whilst vaccine rollout remains in the single percentage digits in the Global South. Whilst the details may change by the year and the decade, this theme remains the same.

Our globalised society is today more interconnected than ever before in human history. As Western citizens, we hold an enormous amount of arbitrary and, if we are honest, unfair influence over global policy. A true empathy for those we share our planet with requires ethnical consumption and lobbying of our political establishments. With continued activism and the judicious application of pressure, real and lasting change is possible in our world. From our success in reversing damage to the Ozone Layer to the end of Apartheid in South Africa, our collective empathy has proven its ability to deliver such change.

Let me end, then, with a call to action: let us try and implement three acts of empathy in every day, on any of the levels I have discussed. Personal, societal or international empathy possess the very real power to change our world, to build bridges over divides and to heal our troubled world. We have tried suspicion and hatred, the results litter the pages of the history books. Let’s work towards a brighter future with empathy.

Shaykh Dr. Umar Al-Qadri

Chairperson Irish Muslim Peace & Integration Council